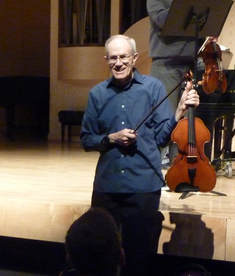

Forty years ago, I switched from violin to viola. Jeff Irvine – fresh from a master’s degree at Eastman – was my first viola teacher, and the best string teacher I ever had. Several years later he became my sister-in-law’s viola professor at Oberlin Conservatory. And this last weekend we were all together at the Viola Festival at UNLV, where Kate is the viola professor.  Jeff with his Iizuka viola Jeff with his Iizuka viola Jeff was the featured guest, escaping from the snowy weather in Cleveland for a few days in the Nevada sunshine. He gave a master class, played in the viola choir, and hung out with Kate and me. Just as I remember him, Jeff is kind, generous, and engaging. He obviously cares about the people he is working with. He always starts with positive feedback before identifying the weaknesses. He asks questions, uses insightful analogies, demonstrates and coaches through new techniques and approaches to problem solving. Jeff was the first teacher who walked all around me while I played, observing my form from all angles and correcting a bow hold here or a neck tilt there. It was unnerving at first, but he caught things my previous string teachers hadn’t noticed for years. I soon came to appreciate his unconventional style, and rapidly improved. Cuban American violist Yunior Lopez gave the master class for high school students from the community. In addition to performing and teaching viola students, he is the founder and conductor of the Young Artists Orchestra in Las Vegas. I didn't get a photo of his master class, but you can check out these excellent performances by Yunior and a few of his high school musicians: Bach Chaconne for Four Violas and Brandenburg #6. If you’re not sure you like the sound of the viola, listen to a viola choir – you will develop a new appreciation for this beautiful, rich sounding instrument. Twenty-five of us gathered on the stage to play a few pieces, where finally, with no violins in sight, we got to play the melody. And that melody wasn’t just for the Viola 1 part: violists are nice people, and we like sharing. Each of the four parts took turns playing melody, harmony, and accompaniment.  Kate with Jeff and some of her students Kate with Jeff and some of her students It was a great group of violists – visiting professionals, teachers and musicians from the community, college students and high school students. And Joey, the extremely well-behaved black Pomeranian mix, who wandered among us on stage during the viola choir rehearsal wagging his tail and enjoying the beautiful music. Hopefully, this will become an annual event!

0 Comments

Fingering: One of the first things for more advanced students to do – when the basics I’ve already described become second nature – is look through the music to see what notes go higher than first position. Once you are used to shifting you will be able to figure out a good place to shift up and when to shift down. And if you can figure this out before you get there, you won’t need to stop and figure it out. Articulations, Dynamics, and Other Nuances: For more advanced music and musicians, you’ll want to look at the markings the composer has written into the music – e.g. slurs, staccato or spiccato, up-bows and down-bows; mezzo-pianos and fortes and crescendos; fermatas and caesuras and ritards; and so on. Just take a quick look over the page to be aware of what’s coming up so it won’t take you by surprise. Intervals: Musicians who have had ear training have a huge advantage over those who haven’t. If you’re one of the lucky ones, you can hear intervals in your head when you look at the notes. This helps you anticipate what the next note is going to sound like. When your eyes, ears, and fingers are all helping, you will be much more fluent in your note reading. Scale degrees: For more advanced students, I ask them to look at what note the piece starts on. Where in the scale is that note? Musicians who know their scale degrees and intervals can hear it in their heads, and can hum the music out loud. Eventually, your goal is to read music the way you read a book. You don’t know how the story goes before you turn to Chapter 1, right? But as you read the words, the story unfolds. You can hear the words and get pictures in your mind as you read. Sight reading music is the same: by looking at the music, you will hear it and feel it without playing a single note.  Over the last two months I have been writing about sight-reading skills. First I discussed the importance of developing these skills, and the levels of ability. Next I outlined the basics I start with when teaching young and less advanced students. Here, I go into more detail, and I'll post a bonus section for more advanced musicians next month. More details about key signature Major & Minor Keys: Usually at first, we are just working with major keys. But when we come across a minor key, I explain the concept of relative minor and show the student how to find the minor key a minor third down. It’s a little tricky for younger and less experienced students to understand, but with repetition everyone gets it eventually. To explain the concept of relative minors, I talk about relatives having the same signature – the same last name – but are different people. This helps students remember that E minor and G major, for example, are relatives; they have the same last name and “sign their names the same way” – with an F#. Next I point out that a lot of music starts and ends on the tonic (e.g. C is the tonic in C major). Not always, but it’s a clue if you’re not sure (and might be a clue that this one is in the relative minor). And I have them find the lowest of that note on their instrument and play a scale in that key so they orient their ear. Accidentals: I ask students to look for accidentals, so they’re ready when they get to them. And I ask: Will you just slide your finger up or down when you get to that note, or is that going to be an extra wide stretch from first to third finger, or…? Those might just be chromatic notes, or they might indicate a modulation to another key. More details about rhythm and meter Rhythm: In addition to clapping the rhythm, I also have students look for anything unusual; for example, a triplet in 4-4 time, syncopated notes, or ties across a barline. Tempo Marking: We look at the context for the rhythms and meter, because the tempo can have a dramatic effect on how the music sounds and is played.

Form: I might also have students take a step back to look at the big picture, the “road map”.

Putting It All Together Once a student can do all of the basics pretty easily with prompting, I start having them do it silently in their heads. We turn the page to a new piece of music, and I wait while they look at all the basic elements. When they’re ready, they give it a shot (starting with a quick one-octave scale if they want to orient their ear), and then I compliment them on the parts they got right and have them take another look at the sections they missed. The Goal What we are aiming for is a musically expressive rendition of what’s on the page. Slowly (with practice) students move from the music equivalent of “See – Jane – run – see – Dick – run – see – Spot – run” to a dramatic interpretation of whatever the composer wrote. And eventually, musicians learn to do all of this pretty quickly. You won’t need to play a quick scale to orient your ear to the key, because you’ll be able to hear the notes in your head and translate that as you play. Things that help:

Have fun, and don’t be in a hurry. You will learn how to do this, but it will take time. If you want, record yourself trying to sight read something today, and then in a year record yourself again. If you have been working on it consistently, you will be amazed at how much better you are!  Last month I wrote about the importance of sight-reading skills and the different levels of ability. It’s a complex skill that involves more than just the ability to read notes and note values correctly on a sheet of music. It also requires musical instinct and an engaged musical ear, just like with learning and playing music by ear with no music in front of you. Although it does take time to learn sight-reading skills, and even more time to develop confidence in your ability, there are specific things you can do beyond just using your musical instinct and your ear. This post describes how I have been teaching my students to approach a new piece of music they have never heard before. Note Names and Note Values: The first thing students must learn is what notes they are playing (the note names, not just what finger to use on what string) and how long that note lasts. I ask questions such as:

These are the basic elements students need to know before I start teaching them to sight-read. I have found that my former Suzuki students are a little hazy on some of this, even though their playing is quite advanced. For example, they might or might not know that that note is called an 8th note, though they probably know it is faster than a quarter note. Because they have learned the music by ear first, and then are using the printed music as a reminder of how it goes, I need to figure out what gaps they have in their knowledge and fill those gaps in. Next I introduce students to the steps for sight-reading a piece of music. Key Signature: When we turn the page to a new piece, these are the first questions I ask:

Then I have the student figure out what the key is. If it’s sharps, then the key is the note above the last sharp (reading left to right). If it’s flats, then the key is the second-to-last flat. This means there are two keys you have to memorize: C major, which has no flats or sharps, and F major, which has only one flat. I also point out that the first sharp in the sequence is always F# and the first flat is always Bb and the order of the sequences is always the same. Time Signature: The time signature is the first clue to the rhythmic feel of the music.

I have students clap the rhythm while I tap the beat on the stand with my pencil. Or I have them point to the notes while saying the rhythm: “One two-and three four”.

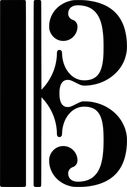

As they get used to these basic elements, I start to add more details. Next month’s post will talk about these details, and I might add a bonus section with some extras for more advanced students.  I have a couple former Suzuki students whom I am teaching to sight-read. Typical of Suzuki students, they are both beautifully set up: perfect left hand form, consistent intonation, excellent bowing technique. But as is also common with Suzuki students, they are not good note readers in spite of their advanced skill. Learning to play “by ear” is an extremely useful skill which I teach to all my students. But learning to read notes is equally important, especially if you want to play in an ensemble or do well in an audition. I think of sight-reading skill in three stages. Beginning: Learning what finger to put down on what string when you see a particular note on a specific line or space, but still needing to hear the melody, either someone else playing it or listening to a recording, in order to understand how it sounds. This is like the child just learning how to read. She’s heard the story before and know how it goes; she could tell it to you herself. And now she has the book in her hands and is learning that that three-letter word starting with a “p” is probably “pig” because the story is about the three little pigs. Competent: Knowing the note names on sight (not figuring it out by using “Every Good Boy Does Fine” or “F-A-C-E”) and playing them accurately (including sharps or flats in the key signature) in “real time”, with correct rhythm. This is the student who can read a book out loud in his reading group, even if he doesn’t know the story yet, with the teacher there listening to correct pronunciation or help with an unfamiliar word. This student is now starting to know when a vowel is short or long – just like sharps and flats – and can figure out by context how a word should sound. Fluent: Looking at a piece of music and hearing it accurately in your head before you play it. Eventually you want to be able to read any book on your own and understand the story as it unfolds. Unfortunately, a lot of musicians don’t get to this stage until college, when they are forced to take sight singing classes! My former Suzuki students are both at the beginning stage. They know what finger to put down, but aren’t sure when it should be high or low (and why), and they need a significant amount of help with rhythm and counting. Sometimes they write the finger number and string below the notes, or color-code notes to indicate when to play it sharp or flat, but I encourage them to drop these habits as soon as they can. Ironically, these habits are an indication that the student’s ear is disengaged and their musical instincts are asleep. They are simply reading by rote with no musical comprehension, and can’t tell when they make a mistake. However, if you are forced to rely on your ear & instincts while reading music, you will begin to be able to tell if that sharp or flat makes sense in the phrase. It’s this experience – deciding if a note you played makes sense in context – that begins to develop your fluency. The same is true for note values. If you are “feeling the beat” (i.e. your musical instincts and ear are engaged) then you’re less likely to short-change rests or play a series of eighth notes twice as fast or slow as they should be. It is a difficult thing to do at first, especially if you haven’t grown up reading the notes. And developing confidence in your ability to sight read takes time. But there are specific things you can do to build your skill, which, along with using your ear and instincts, can help you become a fluent sight reader. I’ll address these in the next part next month.  A violinist was having lunch with another violinist friend one sunny day. She had come directly from a quartet rehearsal, so she brought her violin with her into the restaurant. While eating, she got a call from the violist in her quartet (whom she had given a ride home). The guy said he had left his viola in her car, and could she please bring it back when convenient. The violinist agreed and said goodbye. Then suddenly she gasped. “Oh don’t worry,” said the other violinist. “He won’t even need it before your next rehearsal.” “No, you don’t understand! It’s a hot day, and so I left the car windows wide open!” Now the other violinist gasped too. “Oh no! If we hurry, maybe we can stop the worst from happening!” Together they ran out to the parking lot. But it was too late. There were five more violas tossed into the backseat. ******** Yes, there are many, many viola jokes. Some of them are quite funny, and (to be honest) apt. But it is still a beautiful and under-appreciated instrument, and I am glad I made the switch from violin to viola. If you’re thinking about trying the viola out, I would probably encourage you to go for it. You can always go back to violin if it isn’t for you. I still play both, and it’s pretty easy to go back and forth. Here are some of the pros, cons, and challenges: Learning the Clef The hardest part for me was learning the alto clef. In terms of note names, it is one note (plus one octave) off from treble clef. In terms of fingering, it is a third off, so third fingers become first fingers and twos become open strings. This was mind-bending for me at first. It was like trying to learn a foreign language where a word sounds almost like a word you already know, but means something completely different. I crammed that first day – slogging through all of my viola parts for several hours – and then, exhausted, slept like a rock that night. The next day things just clicked. Our brains do amazing things while we sleep! Now that I am fluent in both clefs, the alto clef feels more logical to me. Middle C, for example, is right in the middle of the staff. Making the Physical Adjustments A full-size violin is about 14 inches, while a standard viola is 16 to 16½ (though some are larger – even 18 inches long). The bigger the viola, the more resonant the sound, which is particularly important for the C string. So you’ll want to play on the largest size you can comfortably handle. Of course, the longer the viola the more you have to stretch out your fingers to play in tune. It is a case of maximizing within natural limitations: fuller sound without losing playability. If you have at least average length fingers, you’ll be fine. If your fingers are long, playing viola might be even easier for you than violin. If your fingers are short, well, try to find a smaller viola and do the best you can. One of the big differences I noticed when I switched was that the viola is slower to “speak” than the violin, especially on the lower strings. These strings are fatter and less responsive, so you have to work harder to coax the sound out. I found that you can’t bow as quickly and get the same purity in the note. You have to use shorter, slower bow strokes and a bit more bow pressure – but not too much, which will crush the sound. In contrast, the violin is much easier to play! Playing the (Luscious, and Sometimes Boring) Internal Harmonies There is a joke about singers: Q: What is an alto? A: A soprano with a brain. The viola is the alto of the string section; the violinist with a brain. The first violins almost always get the melody, so if you know how the symphony goes, you can guess your way through the main themes. With viola, this won’t work; you have to actually think – and read the notes. Often they don’t make any sense at all by themselves, but there is this wonderful revelation when playing them in context with the other parts. Often the violas get the luscious internal harmonies, the part that makes the music so interesting and beautiful. And yes, sometimes, we are playing “oom-pah-pah” measure after measure and trying not to fall asleep, while the violins trip merrily up and down their fingerboards. It takes character to endure these boring bits, and makes those times when we finally get the melody so much more special. To hear the viola section at its luscious best, grab some tissues and try listening to Beethoven’s 7th symphony, the second movement: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J12zprD7V1k Indulging in Open Strings The legendary violist William Primrose is famous for saying that “The glory of the viola is the open strings.” I agree! Violinists are taught from an early age to “cover the E string” in particular, by using their fourth finger rather than the open string. How freeing it is when switching to viola to just let them all ring. And, oh, the open strings are gorgeous. Coping with the Relative Lack of Literature One undeniable downside to playing the viola is that there is a lot less solo music written for the instrument. Violinists have hundreds of concertos and sonatas; violists have merely dozens, and many of them will never be audience favorites. If you ask a hundred classical music lovers who their top ten favorite composers are, none will say Paul Hindemith or Walter Piston, who composed several pieces in the standard viola repertoire. Their music is simply less melodic, and therefore less enjoyable for most people to listen to. Violists make up for this lack by borrowing music from other instruments: for example, the Bach Suites and Rachmaninoff’s Vocalise for cello; a couple of clarinet sonatas by Brahms; Schumann’s Adagio & Allegro for horn; and a few from now-obsolete instruments: Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata (yes, there was an instrument called the arpeggione) and Bach’s Gamba Sonatas. (To be fair, the gamba isn’t exactly obsolete, but people pretty much stopped writing music for it after Bach’s time.) All of these work pretty well on the viola. Enjoying the Camaraderie I have found violists to be a more friendly and approachable bunch of people than violinists. The instrument does tend to attract a different personality: someone who doesn’t need to be in the limelight, who is happy in a supporting role, who is motivated to seek out less obvious treasures, who will patiently wait for the exciting parts. This is, of course, a stereotype, and like other stereotypes it is often, though not always, true. There are violists who are soloists at heart, who have big egos, are territorial, sometimes misanthropic. And there are plenty of violinists who are humble and get along with everyone. However, most of the viola sections I have played with have had a sort of “we’re all in this together” team spirit that I don’t remember experiencing as a violinist. We just have more fun, and seem to like each other more. The “Required Viola Year” I once heard of a violin teacher who made all her students take a year off and learn viola. Some approached their viola year as if they were fulfilling an unpleasant but necessary obligation. Some were surprised at how much they liked it, and decided to keep going. (Her studio had a lot more violists than others like me who teach both.) All, however, benefitted from the experience: increased sensitivity in the bow arm/hand after working harder to coax the sound out of the viola’s fatter strings, a new appreciation for and awareness of the internal parts in an orchestra, more nuanced vibrato, and more. If you get the opportunity, I highly recommend taking the plunge. Just see what happens. And just ignore the viola jokes. In fact, I’ll leave you with one of the other kind… Q: Why are violas bigger than violins? A: They’re not; the violinists’ heads are bigger. :-D  Some of the best ideas come from my students' parents. Here are a few. The Sticker Practice Chart I often have my students use practice charts, but Sara recently made an especially clever one for her daughter: it uses stickers for every day of the week, not just the days she practices. So in addition to the smiley face stickers (the days she practices), there is an owl sticker for lesson days, a popsicle for days she doesn’t practice, and a rainbow heart for “bonus days” which are any days she practices beyond the required number per week. The genius of this plan is that every day when she puts a sticker on, it reminds her that she either chose to or chose not to practice. If she gets to bedtime and there’s no sticker in the box yet, it reminds her that she didn’t take the time to practice that day. If that was a day she intended to practice, it means she has to pick another day to practice when she intended to skip. And the rainbow hearts are special, so she’s motivated to practice an extra day. The Cell Phone Speaker Kelly, who plays piano, recorded the accompaniment on her phone and brought it to her daughter’s last lesson. We’ve tried this in the past with limited results (it’s pretty easy to drown out a cell phone recording as soon as you start playing violin) but this time she had a little round speaker that plugs into the phone’s earphone jack. She found it online for not a lot of money, and it worked great. Performance Opportunities James, one of my viola students, is a pro at performing, rarely getting nervous in front of an audience. It turns out that his dad, who plays guitar, has been taking him to open mic sessions for years. Often on a Friday night father and son are performing together. These are friendly gatherings with low pressure. When he was younger, he would sing a song. Later when he was learning viola at school, he would play his viola part from orchestra. Now he tries out his recital pieces. It’s all part of the fun. Taking the Tapes Off This is another good idea from Kelly. When it’s time to take off the fingerboard tape and you don’t want all the sticky residue, try putting scotch tape under the strings and over the strip, leaving enough of a “tail” to hold with your fingers. Tamp it down and pull to the side. If there’s any residue, do it again with another piece of tape until there’s no stickiness left on the fingerboard. Scotch tape has a lot less goo in the adhesive, so it works without leaving behind another kind of stickiness. Buying an Instrument at a Garage Sale...or an Antique Store Having grown up in a musicians’ family where things are done “properly”, it never occurred to me that a garage sale is a good source for a musical instrument. However, Rohan’s parents happened to find a viola at a garage sale for $600 which would probably have sold at a violin shop for a few thousand. I think part of the explanation is that people often don’t know the value of musical instrument. And so $600 for an item at a garage sale sounds like a lot of money. Another possible reason is that, if they had tried to sell the instrument for what it was worth, it probably would have taken a while to find a buyer; certainly not as quickly as gone in a weekend! And the shop would have taken a commission. Thad & Linda had a similar experience when they found an old violin in an antique shop on their honeymoon. It was $50 and not in playable condition, but it looked cool and was a nice souvenir from the trip. Years later their daughter was playing a rental violin, and Thad took the old violin to a luthier and said “Can you make this thing playable?”. A few hundred dollars later, they had a pretty decent violin, and everyone liked it better than the rental in blind tests. Of course, these are flukes. You could look for a very long time for such a deal when you actually need the instrument now, and you could just as easily end up with a piece of junk. But if you happen to be in the neighborhood, it doesn’t hurt to look. The Sponge Rubber Band I can’t remember who showed me this, but it is brilliant and I have been using it ever since. (Maybe most of you already knew this and I’m just slow…) For the younger players who are using a sponge shoulder rest, get a rubber band big and elastic enough to stretch into a triangle rather than just across in one direction. This keeps the sponge much more stable. Also, Elizabeth showed me that ponytail rubber bands work too if you find one big enough. And Sara showed me how to connect it to the tailpiece cord so it’s always there.  Over the years I have written quite a few arrangements and original compositions for the various ensembles I’ve played with. A bunch of them are for viola or violin with guitar and either recorder or Irish whistle, written over the several years I was performing with Acoustic Cadence folk trio. Others are for viola and piano, played at church with my friend Christina at the piano. There are several simple string trios and quartets based on Christmas carols or other church hymns, written for me to play with the young people at church (two of whom are my violin students). Over the summer I also wrote an arrangement of an Irish song for viola and small pipes. That was a blast! Small pipes are like bagpipes except that you can play them indoors without making everyone go deaf and there is a chance that other instruments can be heard at the same time. It’s a neat instrument, with or without drone, and a 9-note range that is basically a scale in A Mixolydian with an extra G at the bottom. I have a piper friend, Lori, whom I’ve wanted to play with for a long time and finally had the time and the opportunity to write something for us. Hopefully there will be a lot more to come for this combination. It sounded great! Then there is the viola choir my sister-in-law Kate is working on starting up in Las Vegas, her new home. She is now the viola professor on the faculty at UNLV, and the viola choir will include her students and anyone in the community who would like to participate. She asked me to write some stuff for them to play. And so I now have four pieces for viola choir. Since I had time on my hands this summer with students gone on vacation, I took some time to set myself up to sell sheet music (PDFs) of some of these arrangements and compositions. It’s not simple and straightforward, since a lot of these pieces are “incomplete”. I wrote them with particular people in mind, and so they are strewn with things like “play anything you want here” and some chords because I knew that anything Christina came up with in the moment would be better than I could write for her. So I’ve gone back through several and “finished” them so anyone could play them. Those that are ready are now posted under the “Sheet Music” tab on my website. Click on the links to hear them on SoundCloud (just midi files at this point, not live performances yet). If you’re interested in purchasing any, contact me. I’ll send you the music as a PDF.  The Audition A woman I know was telling me about her daughter, who grew up playing the piano. She loved playing, and was very good, even winning state-wide piano competitions in high school. And she was invited to audition at one of the top music conservatories. At her audition, one of the professors told her she would never be great. Of all the stupid things to say to a young musician, that has to be one of the most evil. How did he know if she would ever be great or not? And are there really only two choices: great or not great? I mean, great in what way? According to whom? There are so many ways to be great. Unfortunately, this young woman called her parents and told them to sell the piano. They didn’t, but she never played again. Fire vs. Inspire Some people, usually those with more sensitive personalities, who love music deeply, and have a touch (or more) of perfectionism, will take this sort of comment literally. They take it to heart. Not all will call and say “sell the piano”, but many will falter over the next few months or years, never overcoming the self-doubt that was planted that day. It kicks the dream in the gut; it puts barbed wire around a budding talent. I told this story to my dad, a pianist and college professor who has sat through thousands of auditions. He said “Some teachers will say things like that to light a fire under the student. But I don’t like it.” Agreed. It's a bad way to motivate someone. Fire burns and blows things up. Even if you don’t have a sensitive personality, this motivates you with fear rather than inspiring you. The two might look the same on the surface, but they are quite different underneath. The word “inspire” literally means “to breathe into”. In the creation story, God formed man out of the clay and then breathed into him to bring him to life. This is what it means to inspire; your talent is brought to life by something or someone breathing into it. You become the person you are. Fire, in contrast, sucks the oxygen out of everything nearby. The musician who is motivated by fear becomes needy: he needs constant recognition, repeated reassurance that what that blankety-blank professor said at his audition isn’t true after all. He’s not living the dream, he’s trying to prove someone wrong. The focus of the musician who is inspired is completely the opposite of the person who has a fire lit under her. The former gives her music away, free to share who she is with others, and enjoying the giving as much as her audience enjoys the receiving. The latter craves something from the audience that is never really enough. The audience might still enjoy the performance, but the musician’s thoughts are on her critics rather than the beautiful music. A Different Way If you have a choice, and you usually do, say positive things. Offer correction with the attitude that the student is capable of improving. When you tell him he needs to work harder, tell him it’s because he could be really great, and you are going to help him get there. If her goals are unrealistic, help her to develop a vision for her future that is authentic to who she is. Tell her what she is naturally good at rather than telling her what she will never be. There is not one arbitrary standard of “great”. There are many different styles, characteristics, and qualities. There are many different kinds of audiences, with different preferences and opinions about what is “great”. There are many roles for pianists: soloist, chamber ensemble, accompanist, vocal coach, teacher, and so on. Some become composers, conductors, or theory professors. Some become administrators and run music camps or concert series. And there are many different kinds of music to play, not just the kinds the music conservatory professor approves of. Still Great Though my friend’s daughter had a sad ending to her music career, her story does have a happy ending. At first, she spent four years getting an academic degree in something completely unrelated to music (and which she had no interest in at all). But then, she applied that dedication that had helped her become so good on the piano to raising and training agility dogs. And she is great. She and her dogs have won many international competitions and she has become one of the most sought-after agility trainers in the world. In the world. I hope someday she will play the piano again. Even if it is just for her own pleasure. Occasionally I have a student who has a habit of negative self-talk. When I ask her to play something slightly challenging, she responds: “I’m going to mess it up, I just know it.” Or he makes a mistake, stops, and says, “I’m so stupid.” When I hear this kind of talk, it’s time for The Lecture on Positive Self-Talk.

Saying positive things when talking to yourself might sound like woo-woo psychobabble, but it is actually quite important. Let me explain. You might be familiar with what we know about the left and right hemispheres of the brain. But in case you don’t, here is a very high-level summary: Generally speaking, the left hemisphere is logical, sequential, analytical, and is responsible for producing speech. The right hemisphere is spatial, global, conceptual, and though it is great at processing emotional content and can understand what words mean, it is generally incapable of forming a word, much less a grammatically correct sentence. If you say (with your left hemisphere) “I’m stupid”, even if you are kidding, your right hemisphere hears this. And it is not capable of critical analysis. Say things like this over and over, and it will eventually begin to permeate how you see yourself. False modesty is not a virtue! If you have just performed and someone from the audience compliments your playing, just say “Thank you. I’m glad you liked it.” If you want to be truly modest, follow this up by asking a question to get the other person talking. I even make a habit of saying things in an unambiguously positive way whenever possible. For example, you could say “That wasn’t terrible” or you can say “That was really good.” Go for the second option! At the same time, I am not a fan of over-the-top self-congratulations. It isn’t very helpful, in my opinion, to make a habit of saying “I’m the best!” over and over until it becomes true. Comparison, even in an apparently “positive” way, is dangerous. It may never be true, and you really have no control over your abilities in relation to others. Better to simply say “That was very good”, which is true, believable, repeatable, and is based on variables you actually have control over (like regular practicing). And so, in my music studio, we have a zero-tolerance policy for self-denigration. If I catch you putting yourself down, even subtly, I will make you say the positive opposite three times! |

AuthorQuodlibet: A piece employing several well-known tunes from various sources, performed either simultaneously or in succession. (Schirmer Pocket Manual of Musical Terms) Archives

September 2022

Categories |

|

2024 Bryn Cannon

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed